University of Calgary

SHE WAS BORN Doris Webber in London, England in 1902 and died, with a longleft husband's surname and an affected "e" added to her christened name, in Beijing, China in 1980. In between, she lived 31 years in Canada (1926–57), filling the roles of rural teacher, farmer, political activist, Member of Parliament, party worker.

SHE WAS BORN Doris Webber in London, England in 1902 and died, with a longleft husband's surname and an affected "e" added to her christened name, in Beijing, China in 1980. In between, she lived 31 years in Canada (1926–57), filling the roles of rural teacher, farmer, political activist, Member of Parliament, party worker.

What motivates someone like Dorise Nielsen? Certainly her experience as unhappy wife to an unsuccessful dirt farmer in a place (northern Saskatchewan) and time (Depression) guaranteed to leave only the moribund unpoliticized was a defining factor, but I think only in terms of the direction she took, not in terms of the general manner in which she lived her life. Johnston locates Nielsen's modus operandi in a "great restlessness" and provides information that indicates her family found her challenging even before she left England. Her largely uninformed plan to emigrate to remote Saskatchewan evoked distress from her mother, derision from her brother, and stubborn determination from Dorise, once she became aware of their resistance. For someone who spent her life working for that most intellectually identified of international movements – Marxism expressed in the political arena in variously named versions of communism – Dorise always in the end stayed true to her feelings. Hers was a life committed to romantic adventure and when the communist movement in Canada could no longer provide enough excitement to keep up her adrenaline levels, she re-emigrated, upping the ante not only by going yet again to an arena that guaranteed an uncertain future but somewhere where she did not even speak the language.

Indeed, in the 23 years Dorise Nielsen spent in China, she never really mastered the language. She supported herself modeling the speaking of English to party workers being educated for international contact and correcting fractured idioms in documents and communications translated for official purposes. But it is also clear that a major role Dorise played in Beijing was that of a leading member of a showcase of resident and subsidized foreigners, westerners prized for their dedication to the cause and used as public symbols of international support for Mao's regime. The conclusion that she relished this role as a figurehead committed to communist ideals is supported by the fact that she never seriously considered leaving, rolled without great personal angst with the punches of the Cultural Revolution, and handily wrote off long friendships with people who could not keep the faith, at least not without doubts and the asking of awkward questions. At the end, she was given a memorial service at the cemetery for revolutionary heroes. In this, she managed a continuity of acceptance not commonplace to others in her expatriate community.

I may have made her sound like an adventuress, which of course she was, but she could have chosen to live a life committed to a less admirable ideal than that of everyone contributing what they can to their society and taking back only what they need. Beyond that, Johnston contends that Dorise likely incorporated little from Marxism into her own intellectual makeup, despite committed, decades-long study and note-taking. For this reason, it is unlikely that she struggled much with the wavering nature of the party line. She probably did not have deep intellectual needs for clarity and logic. What she did seem to understand instinctually however was the importance of discipline as an anchor for a, well, restless personality. Her dogged dedication to living out the textbook life of a "communist" is her most apparent demonstration of awareness of herself as someone who, if left to drift, would do so.

There were four children in all this, one of whom died in the meaningless tragedy too many prairie pioneers were doomed to act out. The other three had erratic childhoods and were pursued in adulthood by the demons that unhappy childhoods breed. Paternal alcoholism and maternal restlessness reproduced themselves in various guises at various times in Dorise and Peter Nielsen's descendants. Still, it is difficult to imagine a trouble-free life for children born into a grinding poverty that their parents had not prepared for, that their parents had no control over, and that precious few other people seemed concerned enough about to do anything.

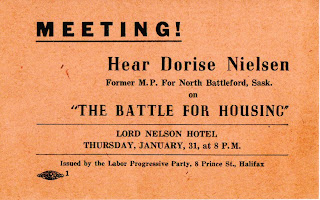

Describing the desperate circumstances of parts of the prairies during the Depression is one of the many things Faith Johnston does well in this biography. People were forced into taking actions that were both distressing and necessary. Children were boarded out with strangers, wives stayed with husbands who had lovers, fathers left and were virtually never heard from again. In all this, Dorise Nielsen had a wonderful piece of luck that allowed her to support her children and also to allow her to use her god-given gifts in a way that was meaningful to her. A talented and attractive speaker, Dorise Nielsen became a political propagandist and for one term during World War II, was Canada's first Communist and third female to serve as a member of the House of Commons.

It was the instability of Saskatchewan political weather in the late thirties that provided the opportunity for Nielsen's election to the House of Commons in March 1940 as a so-called "unity candidate," meaning hers was a candidacy that had been negotiated among various factions of the fractured prairie left out of which CCF predominance would eventually rise. She was more than able to do justice to the job. Her stamina in the face of endless car trips over bad roads, her ability to take enjoyment in delivering constant slight variances of the same message in community after community, her cheerfulness in times of little food and poor accommodation, the fact that she cleaned up well on a non-existent budget for clothes and hygiene, her acceptance without sentimentality that her need to make a living for them must inevitably mean hard times for her children, all these were of great worth to the Communist Party of Canada, with which she was first secretly and later openly affiliated. Blessed with an acolyte's ability to follow the party line (which in this period included dancing to the changes of Stalin's relationship with Hitler), Nielsen seemed to be able to turn on a dime and to take just as much enjoyment in driving a point home one day that she had cheerfully and wittily refuted the day before. That her speeches were a delight is not in question. Even the Mounties who were spying on her said so in their reports. The CPC had a good show woman and it used her in every way that it could.

"Use" was of course the operative word. As soon as Fred Rose entered the House by way of a by-election in Québec, Dorise found herself juniored. Failing to find re-election in 1945, Dorise had to accept being centred in Toronto as part of working for the party, despite her years of effective service in the west. Faced with a wide variety of issues it wanted to talk about, the party relegated Dorise to women's issues. All this, despite the fact that she was the big draw for public lectures. She pulled in the crowd but it was the boys who got to go for glory.

By 1955, by which time her youngest child was 21, Dorise left Canada looking for a more authentic revolutionary experience. After a period in England, she and the man who had been for some time her significant other, stumbled towards Beijing, where she found her last career. Johnston comments on the loneliness that marked Nielsen's last years there but isolation was always a continuing theme in her life. She was at odds as a child with her family, frustrated in post-WWI England with its dearth of men, an English urban immigrant who felt keenly the brutality of prairie life, estranged in turn from a husband and two lovers, estranged repeatedly from her children, estranged from her fellow communist expats. Estranged.

This was not a happy life but it was a purposeful one. Dorise Nielsen chose her track and remained committed to it. It was also madly interesting. Names of Canada's left abound in the book: Buck, Rose, Kashtan, Lewis. And of course a host of others they dealt with. Johnston's research has been painstaking and she has presented the political story without making it all sound like some sort of sporting tournament, a frequent fault of historians who ask us to confuse drudging through detail with watching the game.

Faith Johnston has made a valuable contribution to various streams in Canadian historiography. This book informs us on aspects of women, the left, the west, and on Canada's place in international communism. And, not least, it introduces us to a fascinating character, one whose restless life is worth the telling, in and of itself.

Labour/ Le Travail

No comments:

Post a Comment